March marks the one year anniversary of the first confirmed case of coronavirus infection in the country. Although I never ended up ventilating friends and family in a makeshift tent on the Camps Bay sports fields as I had feared at some point in 2021, life is still far from normal in the majority of the world’s 195 countries.

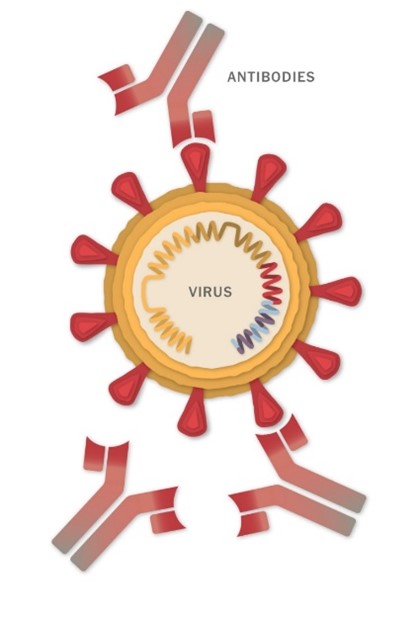

The name coronavirus stems from the Latin word ‘coronam’, meaning crown. All coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, have a ‘crown’ of spike proteins on their surface, like pins on a pin cushion. These spike proteins make a tempting target for potential vaccines and treatments.

![]() Vaccines explained simply

Vaccines explained simply

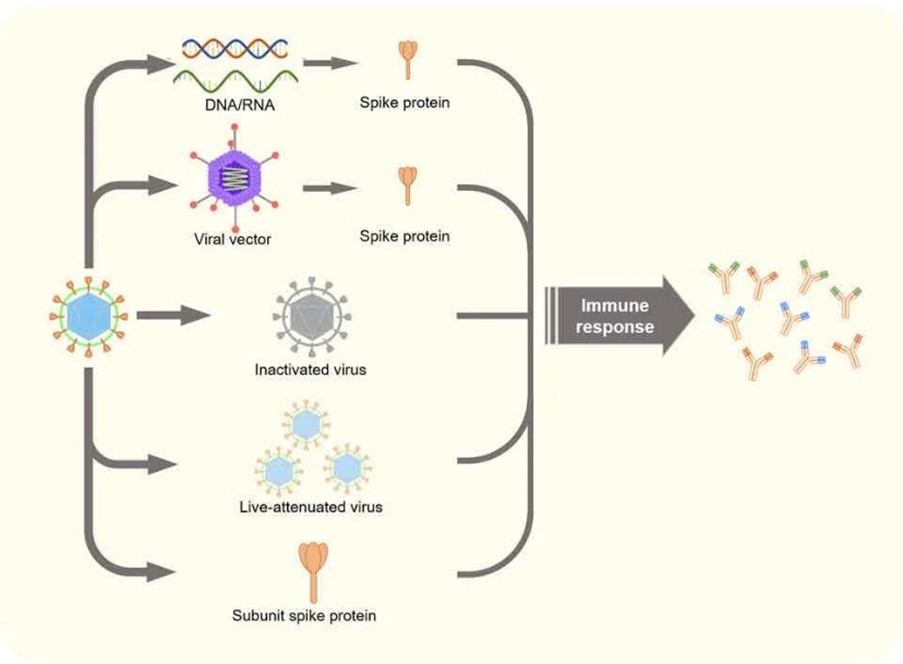

A vaccine is a biological product that stimulates your immune system to produce antibodies, exactly like it would if you were exposed to the disease. These antibodies are proteins that circulate in the blood and quickly recognise and disable a virus or bacteria, thereby preventing or minimising illness.

Each vaccine aims to use a slightly different approach to prepare your immune system to recognise and fight SARS- CoV-2 infection. There are currently close to 200 potential COVID- 19 vaccines in some stage of testing around the world.

The leading vaccines all deliver part of the coronavirus’s genetic material into the body’s cells, leading the cells to produce copies of part of the virus – the spike protein – that the body can then mount an immune response against.

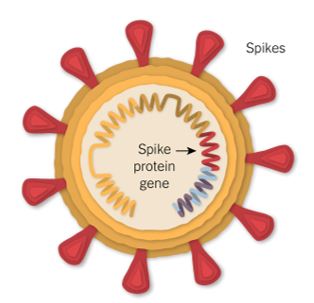

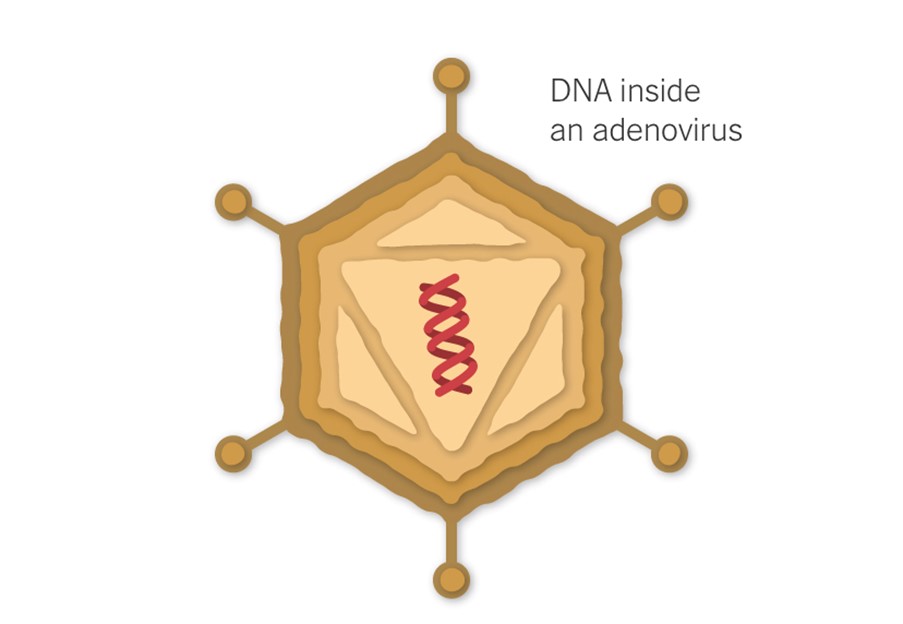

The Johnson and Johnson and Oxford vaccines store the virus’s genetic instructions for building a spike protein in double stranded DNA whereas the Pfizer/ BioNTech and Moderna use single- stranded RNA. These genetic instructions then need to be delivered into and incorporated into cells.

The Oxford (and Johnson and Johnson) vaccine makes this delivery using an adenovirus vector, whereas vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna use an mRNA platform. This is the first time that this technology has been used in a commercial vaccine for humans.

![]() Virus Vectors

Virus Vectors

These vaccines use a virus, often weakened and incapable of causing disease itself, to deliver the gene for the coronavirus spike protein.

The J&J vaccine uses a modified adenovirus (a common cold virus) that can enter cells but can’t replicate inside them or cause illness. The Oxford/ Astra Zeneca vaccine uses a chimpanzee adenovirus.

![]() mRNA Vaccines

mRNA Vaccines

The Pfizer/ Biotech and Moderna vaccines are mRNA vaccines. Your high school biology teacher likely told you that the flow of genetic information in a cell goes from DNA to RNA to protein. m (messenger) RNA are proteins in your cells whose job it is to go into the nucleus and write down the specific instructions for certain tasks. The mRNA vaccines don’t involve the virus or its proteins directly but rather trick your cells into making the proteins. This involves injecting RNA enveloped in a lipid film directly into your cells. This then gets your cells to make the pathogen proteins and those proteins then induce your immune system to develop resistance to the relevant pathogen. So in a sense, your cells make the vaccine.

Other vaccine technologies being employed include using live- attenuated virus, and using a viral protein subunit. The viral vector vaccines are more robust and don’t need to be stored at very low temperatures.

![]() This table comparing the 4 leading vaccines should make you sound informed at your next dinner party.

This table comparing the 4 leading vaccines should make you sound informed at your next dinner party.

| COMPANY | TYPE | DOSES | EFFICACY | STORAGE | COST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford/ AZ | Viral vector | 2 | 62-90% | Reg fridge temperature | R60 per jab |

| Moderna | RNA | 2 | 95% | -20 C | R500 per jab |

| J & J | Viral vector | 1 | 85% (severe infection) | Regular fridge temperature | R150 per jab Free currently |

| Pfizer/ Biotech | RNA | 2 | 95% | -70% | R300 per jab |

| Sputnik | Viral vector | 2 | 92% | Regular fridge temperature | R150 per jab |

NOTE: Comparing the efficacy of these vaccines is challenging because of differences in the designs of the Phase 3 clinical tests — essentially the trials were testing for different outcomes. Pfizer’s and Moderna’s trials both tested for any symptomatic Covid infection.

JnJ, by contrast, sought to determine whether one dose of its vaccine protected against moderate to severe Covid illness — defined as a combination of a positive test and at least one symptom such as shortness of breath, beginning from 14 or 28 days after the single shot. (The company collected data for both.)

Because of the difference in the trials, making direct comparisons is a bit like comparing apples and oranges. Additionally, Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccines were tested before the emergence of the troubling new variants in Britain, South Africa, and Brazil. It’s not entirely clear how well they will work against these mutated viruses.

The JnJ vaccine was still being tested when the variants were making the rounds. Much of the data generated in the South African arm of the JnJ trial involved people who were infected with the variant first seen in South Africa, called B.1.351.

The JnJ one-dose vaccine was shown to be 66% protective against moderate to severe Covid infections overall from 28 days after injection, though there was variability based on geographic locations. The vaccine was 72% protective in the United States, 66% protective in South America, and 57% protective in South Africa.

But the vaccine was shown to be 85% protective against severe disease, with no differences across the eight countries or three regions in the study, nor across age groups among trial participants. And there were no hospitalizations or deaths in the vaccine arm of the trial after the 28-day period in which immunity developed.

It’s not yet known if any of these vaccines prevent asymptomatic infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Nor is it known if vaccinated people can transmit the virus if they do become infected but don’t show symptoms.

![]() The South African perspective- let’s talk numbers and variants

The South African perspective- let’s talk numbers and variants

Sisonke (meaning “together” in Zulu), SA’s national vaccine rollout programme commenced on the 17th of February utilising the Johnson and Johnson (JnJ) vaccine. These jabs are currently reserved for health workers who are participating in the SAMRC’s vaccine roll out implementation study, but brings much needed hope to the whole country.

After a rocky start, the JnJ vaccine is truly a remarkable first choice for our country’s National Vaccination Programme for a number of reasons. Firstly, it was tested in a large trial of almost 44 000 people from four continents, of whom 7000 participants were from South Africa. The follow up time corresponded with our second wave- so the study was able to provide data on how the vaccine works against South Africa’s new, and now dominant variant- 501Y.V2. This variant was responsible for 9/10 COVID-19 infections during the second wave in South Africa.

The South African part of the trial demonstrated that the JnJ vaccine provides 57% protection against moderate-severe disease, 85% protection against severe disease and 100 % protection against death. I like the sound of that- 100% protection against death!

Furthermore, viral vector vaccines are tried and tested technology with fairly predictable short and long-term side effects. They are more robust than the mRNA vaccines, so don’t need to be stored at extremely low temperatures. A further significant advantage is that the JnJ vaccine only requires one shot! Aspen Pharmacare has agreed to provide the necessary capacity required for the manufacture of the JnJ vaccine at an existing sterile facility in Port Elizabeth # proudlySouthAfrican # homegrown.

South Africa may possibly and fortuitously have hit the sweet spot of vaccines here- perhaps a case of “Last mover advantage”. Hopefully, by working ‘together’ more than 60 % of South Africans would have been vaccinated by the end of 2021.